THE MUPPET SHOW premiered on CBS on September 20, 1976, four days before Jim Henson’s 40th birthday. It was a strange thing to find in prime time, and not simply because it featured Henson’s silly, strange Muppet creations. Five years earlier, CBS initiated its “rural purge,” cancelling popular and long-running programs like Green Acres, The Beverly Hillbillies, and Hee Haw, in favor of urban-skewed, socially relevant shows like The Mary Tyler Moore Show and All in the Family; the other networks quickly followed suit. Whether or not these executives were dismissive of rural audiences and the older demographic, the success of these new shows points to an understanding of emerging trends; “purge” makes them sound spiteful, when in reality they were responding to changing tastes.

It wasn’t just explicitly rural shows that found themselves without a home, though. Variety shows, a mainstay of television programming from its inception, were losing their audience. The years between 1970 and 1975 saw the cancellation of The Ed Sullivan Show, The Lawrence Welk Show, The Andy Williams Show, and The Dean Martin Show. Young Jim Henson cut his teeth with appearances on Ed Sullivan and The Mike Douglas Show, among others; and he had his big break in the mid-’60s, in the guise of Rowlf the Dog, on The Jimmy Dean Show — precisely the sort of program that would find itself out of favor a decade later.

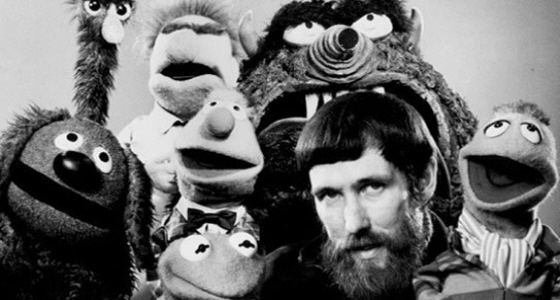

So, while it’s no surprise that Henson would embrace the format, the show’s mere existence, to say nothing of its success, is a testament to Henson’s knack for employing pragmatism and business acumen in the service of imagination and creativity. The man on display in Jim Henson: A Biography is certainly brilliant, ambitious, and possessed of a boundless creativity, but if we’re to employ the word “genius,” as a number of his colleagues do, we must acknowledge that he was more than a visionary or fantasist. It’s no coincidence that Kermit the Frog, Henson’s most famous creation, sings of “the lovers, the dreamers, and me”; for Henson, like his Muppet avatar, existed in his own category. He was a lover, yes, and a dreamer too, but a manifestly practical one. ©

So, while it’s no surprise that Henson would embrace the format, the show’s mere existence, to say nothing of its success, is a testament to Henson’s knack for employing pragmatism and business acumen in the service of imagination and creativity. The man on display in Jim Henson: A Biography is certainly brilliant, ambitious, and possessed of a boundless creativity, but if we’re to employ the word “genius,” as a number of his colleagues do, we must acknowledge that he was more than a visionary or fantasist. It’s no coincidence that Kermit the Frog, Henson’s most famous creation, sings of “the lovers, the dreamers, and me”; for Henson, like his Muppet avatar, existed in his own category. He was a lover, yes, and a dreamer too, but a manifestly practical one. ©So how did he do it? He went where the enthusiasm — and the money — was: England. But that was later. It began with a desire for success and a deep confidence bordering on egotism. At the height of his career, Henson wrote in his journal:

I’ve always known I would be very successful in anything that I decided to do — and it turned out to be puppetry. And not only am I not surprised, but I’m disappointed that it’s taken this long, and I haven’t begun to be as successful as I will be.

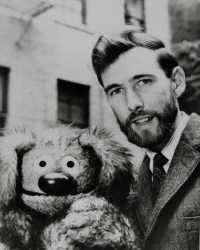

The truth of Henson’s statement is borne out by the full arc of his career, a career that really did just “turn out” to be centered on puppetry. What became his legacy started as a means to an end: at 17, Henson was looking for a way to break into television. He found it in a notice seeking “youngsters […] who can manipulate marionettes” for a new morning show on the local NBC affiliate WTOP in Washington, DC. By 1957, Henson was reaching national audiences with coffee commercials featuring the Muppet duo Wilkins and Wontkins. This advertising work made Henson rich — he drove a Rolls Royce Silver Cloud, purchased used for $5,000, to his college graduation in 1963 — and his dealings with advertisers showed natural business savvy. When Purina offered $100,000 for exclusive rights to Rowlf, who began life shilling dog food, Henson told Bernie Brillstein, his agent and lifelong friend: “[N]ever sell anything I own.”

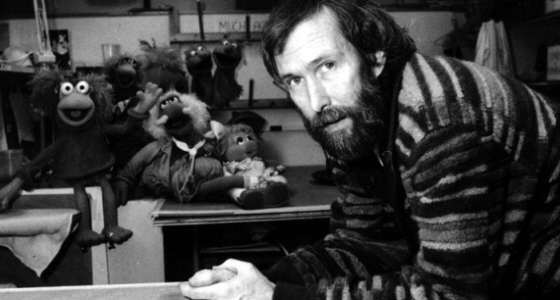

Henson was, in most ways, a quiet man. Brillstein relates that “he never spoke above a whisper” and punctuated his conversation with a gentle hmmm. He was nonconfrontational to a fault; indeed, the slow decay of his marriage to Jane Henson can be traced to his inability to argue, to say or hear a word spoken in anger or spite. And yet he maintained an iron resistance to what might be called selling out, a resistance that paid dividends again and again: that Purina pitch-puppet became Rowlf, a star in his own right; a mock-German spouting cook, created for a USDA exhibition in Germany, became the Swedish Chef; the technology behind the huge, bumbling La Choy Dragon, made to sell canned chow mein, became the prototype for “walkaround” characters like Big Bird and Snuffleupagus; and a Munchos-stealing Muppet was reimagined as Sesame Street’s beloved Cookie Monster.

Henson never discarded a good Muppet — though a few ended up in his children’s toy chest — and he never forgot a good connection. Looking for someone to handle business affairs at Henson Associates, he tapped IBM executive David Lazer, with whom he had worked on various in-house Muppet projects. More important, though, was another connection, one that began with a short-lived collaboration with Julie Andrews. Throughout the 1970s, Henson tried and failed to find a network home for his Muppet variety show. When US TV executives proved resistant, Henson turned to the man who produced The Julie Andrews Hour, British media mogul Lord Lew Grade. It was Grade that gave The Muppet Show a chance; the rest is history. At its height, The Muppet Show was both a critical success and a ratings smash, with a worldwide audience in the hundreds of millions and an appeal that cut across all demographic and cultural lines. (Rumor has it that diplomats working in the USSR’s London embassy would furtively watch the program.)

Read More ….

© Los Angeles Review of Books – Used by Kind Permission - -