©Words Piers Hernu

It is ten past eight on a clear, bright morning in the quiet, coastal town of Horton some forty six miles south of Oslo the capital of Norway, and as a small ferry pulls into the harbour, I stand gazing across sparkling seas at the sunlit green Island of Bastoy shimmering on the horizon less than two miles away. Despite the tranquil setting, its with some trepidation that I step on board the ferry for the twenty minute ride to Norway's only island prison.

Trepidation primarily because the last time I set foot in a prison was some twenty years go in Kathmandu, Nepal whereupon I stayed for the next eight months and five days having been found guilty of the crime of gold smuggling. Three years previously, as part of my law degree at Manchester University, I had been busy studying the English penal system so it had come as something of a shock that a combination of dwindling funds, easy money, crass stupidity and a young man's lust for adventure had conspired to leave me studying the Nepalese penal system at such unexpectedly close quarters.

It is therefore with a complex mix of emotions including equal amounts of dread and curiosity that this time willingly, I cross the rubicon between freedom and incarceration to experience first hand Norway's new, controversial and seemingly successful approach to crime and punishment.

Another factor contributing to my unease is that I am soon to be speaking to a number of Bastoy's inmates, including murderers, bank robbers, violent offenders (and yes some fellow failed smugglers) without any of the usual protection afforded to prison visitors. There are apparently no cells, no bars, no guns, no truncheons and no CCTV cameras on the island to protect a visiting journalist. On the other hand, as a result of a wide variety of jobs that the inmates are given on what is trumpeted as the word's first self sustaining 'Ecological Prison', there are numerous numerous knives, pitchforks, axes and even chainsaws - all freely available to the inmates - with which to kill me.

On board I am greeted by shaven headed prison guard, thirty six year old Sigurd Fredericke, whose job it is to be my guide and protector for today. 'Don't worry,' he grins, shaking my hand with a reassuringly vice-like grip, 'Bastoy is not like any other prison you know.' He pauses, looking furtively around the boat. 'You see that man there,' he whispers, pointing discreetly at one of the three uniformed ferry workers, 'he's one of our inmates – a murderer.'

For many of us in Britain the idea of allowing a convicted murderer the freedom to work and mix freely with non criminals not only sounds like a recipe for bloodshed, it offends our deeply ingrained traditional ideas about prisons as a place of punishment and as a deterrent. That said, our current Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice Kenneth Clarke, recently stated: 'It is just very, very bad value for taxpayers’ money to keep banging them up and warehousing them in overcrowded prisons where most of them get toughened up.' Despite a recent opinion poll clearly showing the British public's hunger for harsher prison conditions, Clarke (and therfore Cameron) are currently trying to tackle the twin problems of over population and reoffending by pushing through far reaching reforms which emphasize shorter sentences whilst placing prisoners in a working environment. Against this domestic backdrop, perhaps it is time we in Britain put our preconceptions on hold and took a long, dispassionate look at the remarkable results that Norway's brave new approach to an age old problem is currently achieving.

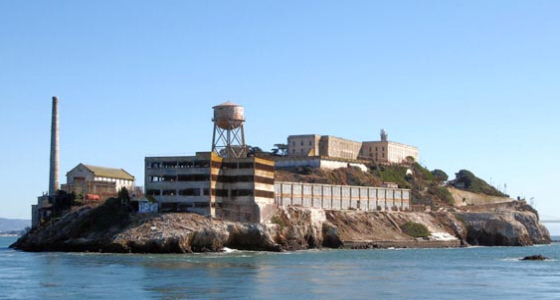

For many of us in Britain the idea of allowing a convicted murderer the freedom to work and mix freely with non criminals not only sounds like a recipe for bloodshed, it offends our deeply ingrained traditional ideas about prisons as a place of punishment and as a deterrent. That said, our current Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice Kenneth Clarke, recently stated: 'It is just very, very bad value for taxpayers’ money to keep banging them up and warehousing them in overcrowded prisons where most of them get toughened up.' Despite a recent opinion poll clearly showing the British public's hunger for harsher prison conditions, Clarke (and therfore Cameron) are currently trying to tackle the twin problems of over population and reoffending by pushing through far reaching reforms which emphasize shorter sentences whilst placing prisoners in a working environment. Against this domestic backdrop, perhaps it is time we in Britain put our preconceptions on hold and took a long, dispassionate look at the remarkable results that Norway's brave new approach to an age old problem is currently achieving. Being an Island prison just off the coast of the mainland, housing some of the country's most hardened criminals, I had envisioned Bastoy as something of a Norwegian Alcatraz but, as we chug ever nearer, and the outline of an old church steeple rises above a backdrop of pristine pines, it becomes clear that Sigurd is absolutely right. Slowly the idyllic sight of a what appears to be a quaint Norwegian village reveals itself complete with cozy cottages, dirt roads and even horses and carts.

Alighting, we climb on to one of the waiting carts and with a shake of the reigns, the driver (48 year old Lars Ulmann, a jovial former amphetamine smuggler serving five years) begins our climb up the winding road towards the church. On the way Sigurd reveals that having previously worked as a guard in one of Norway's conventional 'closed' prisons he left six years ago to pursue a successful career as a property developer. Despite the big salary, car and office, three years later he jumped at the chance when his former job offered him a job on Bastoy. 'Working here is much more rewarding than being a property developer or a conventional prison guard,' he explains, 'because not only do the prisoners have much more freedom and responsibility, the guards do too.'

One hundred yards up the road we pass our first dwelling (one of eighty buildings on the island), a modern bungalow complete with wooden veranda, upon which a man in swimming trunks is stretched out on a sun lounger. It turns out that thirty six year old Nils, who was handed a sixteen and half year sentence for having shot dead a fellow amphetamine smuggler over an unpaid debt, is relaxing between his shifts as a ferry worker: 'I spent eight and a half years in a closed prison before moving here nine months ago and I'm much happier here', he says stating what seems fairly obvious, 'I immediately trained to be a ferry worker which I really enjoy and soon I'm going to start a maritime course at University with the aim of becoming a commercial captain when I get out. It's s a great idea to teach you a new skill for when you get out because normally all you leave with is two garbage bags full of clothes and its like your life has been on pause – you continue with all the bad habits you had before you got in.'

Somewhat stunned by this surreal encounter, I climb back on the cart and we promptly exchange cheery 'hellos' with a group of inmates raking leaves in the church grounds. We pull up next door outside the old white 'administration' building complete with a downstairs 'canteen' that I am soon to discover could, in terms of food and décor, pass for a trendy London restaurant. Upstairs in his neat office, the prison Governor, Arne Kvernvik Nilsen, is keen to explain what this bizzarre place is all about.

'Bastoy is an ongoing experiment the results of which I hope will benefit not only Norway but the UK, Europe and the rest of the world,' he begins and there follows a fascinating hour long discussion with a man whose impressive qualifications for the job are matched by a passionate, almost evangelical zeal for what is clearly a very personal and heartfelt mission.

A qualified and practicing psycho-therapist (specialising in the Gestalt school which emphasizes personal responsibility and self regulation) Nilsen worked in the UK for a year as Lewes prison's chaplain in the early 80s before returning to Norway and working his way up through the probationary services. Twelve years of working for Correctional Services Deparment for Norway's Ministry Of Justice later, he took up the post of Bastoy's new governor in 2007. Nilsen explains that as one of the wealthiest, most sparsely populated and most stable countries in the world, Norway's riches are derived primarily from it being the largest producer of oil and gas per capita outside of the Middle East. With a population of around five million people, Norway's prison population fluctuates around three and a half thousand inmates which is the lowest percentage in Europe apart from Iceland. (Coincidentally Ken Clarke has recently stated that he is looking to reduce the UK's prsion population by 3,500 by 2015 from the current level of 85,361).

'I believe that as human beings if we are prepared to make fundamental changes in the way we think regarding crime and punishment,' he continues, 'then we can dramatically improve the rehabilitation of prisoners and thereby reduce the reoffending rates.'

Nilsen goes on to explain that because the Norwegian penal system has no death penalty or life terms and a maximum sentence of just twenty one years, Norwegian society is forced to confront the fact that most prisoners, however heinous their crimes, will one day be released back into society. As a result by far the most significant statistic for Nilsen and Norway's law abiding citizens is that of reoffending rates. With evident pride he tells me that an extensive new study undertaken by researchers across all the Nordic countries reveals that the reoffending average across Europe is about 70-75%, whilst in Denmark, Sweden and Finland the average is 30%. In Norway alone it is 20% and its jewel in the crown is Bastoy with a reoffending rate of just 16%.

'Both society and the individual simply have to put aside it's desire for revenge,and stop focussing on prisons as places of punishment and pain.' he continues, 'Depriving a person of their freedom for a period of time is sufficient punishment in itself without any need whatsoever for harsh prison conditions. 'Bastoy takes the opposite approach to a conventional prison where prisoners are given no responsibility, locked up, fed and treated like animals and eventually end up behaving like animals. Here you are given personal responsibility and a job and asked to deal with all the challenges that that entails. All over Europe we have seen an increase in prison violence in the last few years but since I have been governor I have not had one violent incident here and yet the staff are not armed in any way. One inmate did manage to escape by stealing our fishing boat one night and his punishment his punishment was to go back to a closed prison. I believe Bastoy is an arena in which the mind can heal allowing prisoners to gain self confidence, establish respect for themselves and in so doing respect for others too.'

'Both society and the individual simply have to put aside it's desire for revenge,and stop focussing on prisons as places of punishment and pain.' he continues, 'Depriving a person of their freedom for a period of time is sufficient punishment in itself without any need whatsoever for harsh prison conditions. 'Bastoy takes the opposite approach to a conventional prison where prisoners are given no responsibility, locked up, fed and treated like animals and eventually end up behaving like animals. Here you are given personal responsibility and a job and asked to deal with all the challenges that that entails. All over Europe we have seen an increase in prison violence in the last few years but since I have been governor I have not had one violent incident here and yet the staff are not armed in any way. One inmate did manage to escape by stealing our fishing boat one night and his punishment his punishment was to go back to a closed prison. I believe Bastoy is an arena in which the mind can heal allowing prisoners to gain self confidence, establish respect for themselves and in so doing respect for others too.'Downstairs its time for the staff's midday lunch which consists of chicken risotto (supplied from Bastoy's expansive chicken shed) a spread of cold meats and cheeses and a wide variety of fresh salad. All the food is prepared and served by the kitchen's inmates who then sit down and eat alongside the guards, administrative staff and even the governor. The canteen itself is light, airy and spacious and decorated with Norwegian art, the centrepiece being an impressiveten foot long model of an old Norwegian merchant ship.

Back in the horse and cart we climb uphill to one of two eighteen bedroom houses where newcomers undergo an introductory week of living training (learn how to make food, clean rooms etc) before gradually dispersing as spaces become available in some of the more private and spacious houses scattered around.

Outside 52 Bjorn Andersen, a former sociology researcher who arrived at Bastoy last week ago after three years in a closed prison, is having a cigarette break from mopping the communal kitchen floor. 'I was married to a nice girl for twenty years and we have five kids but in 2008 she came to me and said she had secretly bought a new apartment and was leaving me. I'm afraid I completely snapped and attacked her,' he says gently shaking his head. 'Luckily she wasn't hurt but I was found guilty of attempted murder. This prison is much better for me because now with access to a computer and the internet I can continue the sociology dissertation I was writing before I was arrested. I get released in January and I feel I'll be much better prepared to go back into real society having already been given back many of the freedoms and responsibilities that I'll have to deal with on the outside.' He explains that from Monday to Friday inmates are responsible for getting up in time to have breakfast,, make themselves a packed lunch and be at their place of work by 8.30. They stop for a half hour lunch break at around 11.30 before ending the working day at 2.30. 'Dinner' is then served at 2.45 in the main hall and the inmates are then free to do whatever they like until 11pm when they must be back in their living quarters. The range of things for prisoners to fill the rest of their day with is simply staggering. Bastoy has tennis courts, a football pitch, a gym and exercise equipment, a sunbed, a sauna, a cinema room, a band rehearsal room and an expansive library or they can stay in the comfort of their double glazed, fully furnished bungalows and watch prison supplied cable TV, DVDs or listen to music. Bjorn tells me he prefers spending his spare time exploring the island itself and its network of paths that snake through the pine forests or the five miles of pebble beaches to swim or fish from.

The angry whine of chainsaws grows steadily louder as we pull up outside Bastoy's team of six forestry workers busily chopping logs for sale on the mainland. Sigurd explains that depending on availability, prisoners generally choose their area of work which can be based on previously learned skills or the desire to acquire new ones. The range of jobs available includes, forestry, farming animals and crops, ferry working, fishing, DIY, laundry, mechanics, rubbish collecting and the prisoners are paid an average of fifty seven kronas a day (around £6.70 in British money). Twenty eight year old Peter, a Dutch truck driver sentenced to six years for smuggling 150kgs in his lorry hashish from the Netherlands takes a break from his work as the team's tractor driver: 'In closed prison I was locked up for twenty three hours a day,' he winces, 'so I'm really happy with this job. I am treated very well here and in return I will treat them very well also. Of course its never nice being in any prison but it could be much, much worse.'

With 120 inmates and seventy staff (35 of which are guards) Bastoy is Norway' largest 'low security prison' but it is one of four others dotted around the country. What makes it unique is that in 2007, in Nilsen's first year as governor, it was declared the World's first 'ecological prison'. He claims that is is this goal of self sufficency which both creates the jobs for prisoners and provides them with a common purpose. 'The prison is not only self sustaining and as green as possible in terms of recycling, solar panels, treating our own sewage, switching from oil to wood fired heaters, using horses instead of cars and etcetera,' he explains, 'but it means that the inmates have plenty to do and plenty of contact with nature – the farm animals, wildlife, the fresh air and sea. We try and teach inmates that they are part of their environment and that if you harm nature or your fellow man it comes back to you.' He adds that a significant advantage of the ecological approach is that due to low staffing levels and producing their own food and fuel, Bastoy is actually the cheapest prison to run in the whole of Norway: 'We have a price for each prison bed in this country and we are much cheaper to run than a conventional closed prison.'

According to Nilsen the principles upon which Bastoy are based can be traced back to a mixture of theories on psychology, sociology and ecology which emerged from the heady hothouse of early 1970s West coast American academia. But the origins are even older: 'I very often quote the old North America Indian, Chief Seattle from 1854,' he grins sagely, 'Man does not weave the web of life – he is merely a strand in it. Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself.'

We pop in on Fred the fifty five year old amphetamine dealer shepherd, who proudly shows off his new lambs and beams 'its a very very nice place to do a sentence.' Next door, the cattle herder Frank 48, a former bank worker who wrote cheques to himself, shows us his new calves. In the laundry house, thirty six year old, burly bank robber Espen is busily pressing floral bed sheets. 'I grew up in and an orphan house and started crime at the age of fifteen,' he tells me through a cloud of steam, 'I've spent thirteen years in different closed prisons but a friend told me about Bastoy so I applied to come here. It is an extraordinary place to both work and learn in. For the first time in my life I feel motivated and I believe in myself – I can see there is another way now and I really believe I can break my circle of crime.'

Fifty year old Gunnar Sorbye is not an inmate but has commuted to the island every day for the last five years as the head of carpentry, plumbing and DIY division. Under him a team of nine prisoners learn the skills he teaches whilst maintaining the buildings on the island: 'I have never really felt like I am working in a prison,' he smiles, 'and nor have I ever felt the slightest bit threatened here. If I was told that my new neighbours were going to be newly released prisoners I would far rather they had spent the last years of their sentence working in Bastoy than rotting in a conventional prison. I think most Norwegians increasingly realise that closed prisons are the old fashioned way of dealing with criminals and that in terms of rehabilitation they simply don't work.'

Fifty year old Gunnar Sorbye is not an inmate but has commuted to the island every day for the last five years as the head of carpentry, plumbing and DIY division. Under him a team of nine prisoners learn the skills he teaches whilst maintaining the buildings on the island: 'I have never really felt like I am working in a prison,' he smiles, 'and nor have I ever felt the slightest bit threatened here. If I was told that my new neighbours were going to be newly released prisoners I would far rather they had spent the last years of their sentence working in Bastoy than rotting in a conventional prison. I think most Norwegians increasingly realise that closed prisons are the old fashioned way of dealing with criminals and that in terms of rehabilitation they simply don't work.' Sigurd shows me around the visiting block which also houses the nurse, the priest, the dentist, the physiotherapist, a creche for small children and nine visiting rooms complete with comfy sofas in each. A chance enquiry as to why there are paper towel dispensers on the walls in each room reveals that prisoners are allowed at least one three hour visit a week and that 'intimate relations' with visitors are allowed not only for Bastoy's prisoners but in fact across the whole Norwegian prison system. Inmates with young children are allowed day long visits from their wives and girlfriends in a special designated house on Saturdays.

Beneath the guard house I am at last shown something that looks genuinely prison like - two small, spartan cells with heavy steel doors and blocked out windows. It is here that prisoners are held if they have broken one of the cardinal rules of Bastoy (ie no violence, alcohol or drugs) before being taken back to a closed prison. Sigurd tells me this place was last used some two years ago for a prisoner found with alcohol in his room.

Finally at ten past three its time to board the ferry back to what, by contrast, seems a very drab and dreary mainland. Behind us only four guards will remain for the night to oversee the one hundred and twenty inmates. I'm joined on deck by the governor who is also heading home and in chatty mood: Because of Bastoy's results the Norwegian government is currently changing the law so that people who receive a sentence of up to four years can serve their whole sentence in a prison like this,' he tells me, 'don't get me wrong there will always be a need for conventional high security prisons for people who are simply too damaged but those people are few and far between. I believe the UK is going in the wrong direction - down a completely mad and hopeless path because you still insist on revenge by putting people into harsh prison conditions which harm them mentally and they leave a worse threat to society than when they entered. This system actually has nothing to do with Norway or islands so I see absolutely no reason why it can be adopted in the UK.' Whatever you think of Nilsen – deluded do gooding hippy, boss of a kind of Butlins for bad boys or perhaps a visionary genius, Bastoy's results, like the prisoners, the guards and indeed the governor, speak for themselves.