The Gang of Four were from Leeds. They were male, they were white, there were four of them, and they played rock music using guitar, bass and drums. And yet the way they approached that music was almost entirely different from anything coming out of London. The guitarist slashed at his instrument as if at random, inventing new chords as he went, while the drummer and bass player frequently hinted that they might be incorporating disco rhythms into the music; verses would have some semblance of order until the choruses would erupt in a mass of repetitive shouted vocals and the listener would be left clueless.

The Gang of Four were unashamedly political. They were named after a breakaway faction of Chinese Communists. They sang not about Saturday’s kids or the modern world but about capitalism and communism, and actually referenced the ‘working classes’ in one song, as if speaking of a distinct species. Their first EP included the song titles ‘Armalite Rifles’ and ‘(Love Like) Anthrax’, words we barely understood. About the only bands you could compare them with were the Mekons – who also hailed from Leeds and had a lyrically confrontational single of their own entitled ‘Never Been in a Riot’ – and, at least for their scratchy guitars, political lyrics and attendance at Leeds University, Scritti Politti.

On the face of it, then, the Gang of Four did not seem commercial. But things quickly happened for them: an acclaimed single on indie label Damaged Goods; a popular session for John Peel. Paul Weller, an early fan, invited them to open for The Jam at the Music Machine (and urged me to get there in time to see them, which I did). And then, in the spring of ’79, they signed to EMI. Immediately, there were letters in the NME noting that EMI was not just Britain’s biggest record company but also one of its biggest weapons manufacturers and that a political band like the Gang of Four should think twice before signing with such a corporation. The Gang of Four, though, like Adam Ant before he left Decca with his tail between his legs after the dismal failure of ‘Young Parisians’, saw their deal – especially the size of their deal – as a victory for the oppressed masses over their corporate bosses. They even presented the precise terms of their lucrative contract to the British music press, right down to the compli¬cated process of ‘options’, as if they were the first band from the north of England since punk happened to sign with a major record label – and who knows, perhaps they were.

On the face of it, then, the Gang of Four did not seem commercial. But things quickly happened for them: an acclaimed single on indie label Damaged Goods; a popular session for John Peel. Paul Weller, an early fan, invited them to open for The Jam at the Music Machine (and urged me to get there in time to see them, which I did). And then, in the spring of ’79, they signed to EMI. Immediately, there were letters in the NME noting that EMI was not just Britain’s biggest record company but also one of its biggest weapons manufacturers and that a political band like the Gang of Four should think twice before signing with such a corporation. The Gang of Four, though, like Adam Ant before he left Decca with his tail between his legs after the dismal failure of ‘Young Parisians’, saw their deal – especially the size of their deal – as a victory for the oppressed masses over their corporate bosses. They even presented the precise terms of their lucrative contract to the British music press, right down to the compli¬cated process of ‘options’, as if they were the first band from the north of England since punk happened to sign with a major record label – and who knows, perhaps they were.But then they released their first EMI single, ‘At Home He’s a Tourist’, and came abruptly up against reality. The original words to the song, as heard on their Peel session, referenced Durex ‘in your top left pocket’. By the time it came out on vinyl, the specific brand had been replaced by the word ‘rubbers’, apparently at EMI’s insistence. This still did not satisfy the Top of the Pops producers who, panicking at the potentially permissive effect of mentioning condoms to millions of pubescent wankers, insisted the Gang of Four change it, again, this time to ‘rubbish’. The group, probably wondering if they might not be better off in totalitarian China after all, walked off the show rather than compromise further. They got tons of good press for doing so, but ‘At Home He’s a Tourist’ stalled at number fifty-eight and the odds of them being invited back on Top of the Pops in the future were placed at zero. So much for changing the system from within.

That was one of the problems with Top of the Pops – it played such an important part in the hit-making process, largely because there was almost no other opportunity to see a decent band on television (other than The Old Grey Whistle Test, which appeared stuck in the year 1975). But then Something Else came along. Broadcast on BBC2, from a different city every Saturday night, Something Else claimed to be handing over the production reins to local youth. It didn’t do anything of the sort, really – there was a reason the BBC was known as ‘Auntie’ – but still, it made a welcome change to have some spotty teenager stumbling over his or her cues than Janet Street-Porter or Whispering Bob Harris condescending to us. And Something Else did, indeed, have something else: live bands. Good ones. Great ones. Including, on the same night in September 1979, The Jam and Joy Division.

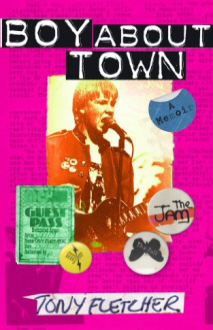

© Words Tony Fletcher

Available on 4th July – Buy here From Amazon