Jay Dobrin is a true original of British Martial Arts. In an era of 'health & safety' and lawsuits; of padded sticks, aluminium or rubber knives and protective equipment; of mass marketing, aimed at filling dojos with pre-pubescents and their free-spending parents, Jay teaches reality-based self-defence to a select few; using real sharpened blades and baseball bats. His thinking is simple...help people to protect themselves from life's predators via using the brutal but effective teaching methods of the Philippines; real weapons, wielded with aggressive intent, in the belief that this will better prepare his students for bullies, muggers, rapists, potential murderers and the rest of society's low-life. What follows is a profile of this unique instructor, incorporating his thoughts on dealing with fear and his memories of forty years of martial arts training and instructing. I. Searching for that 'certain something'.

Jay Dobrin was born in November, 1949, in Hackney, East London. Dobrin's teen years were marked by almost constant street-fighting and Jay's father suggested to his fiery-tempered son that he try some form of 'organised fighting', in order that he might channel his aggression more constructively.

However, neither western boxing nor Aikido, Judo or Karate satisfied Dobrin's quest for a form of 'legal combat' which could adequately replicate the adrenalin-rush of the street fights which Jay regularly engaged in.

In his early twenties Dobrin was still looking for that elusive combat form to satisfy his innate aggression when, by one of those 'lucky accidents' which can shape a person's fate, Jay was driving around the streets of Hackney one evening when he noticed a large group of people entering a community hall.

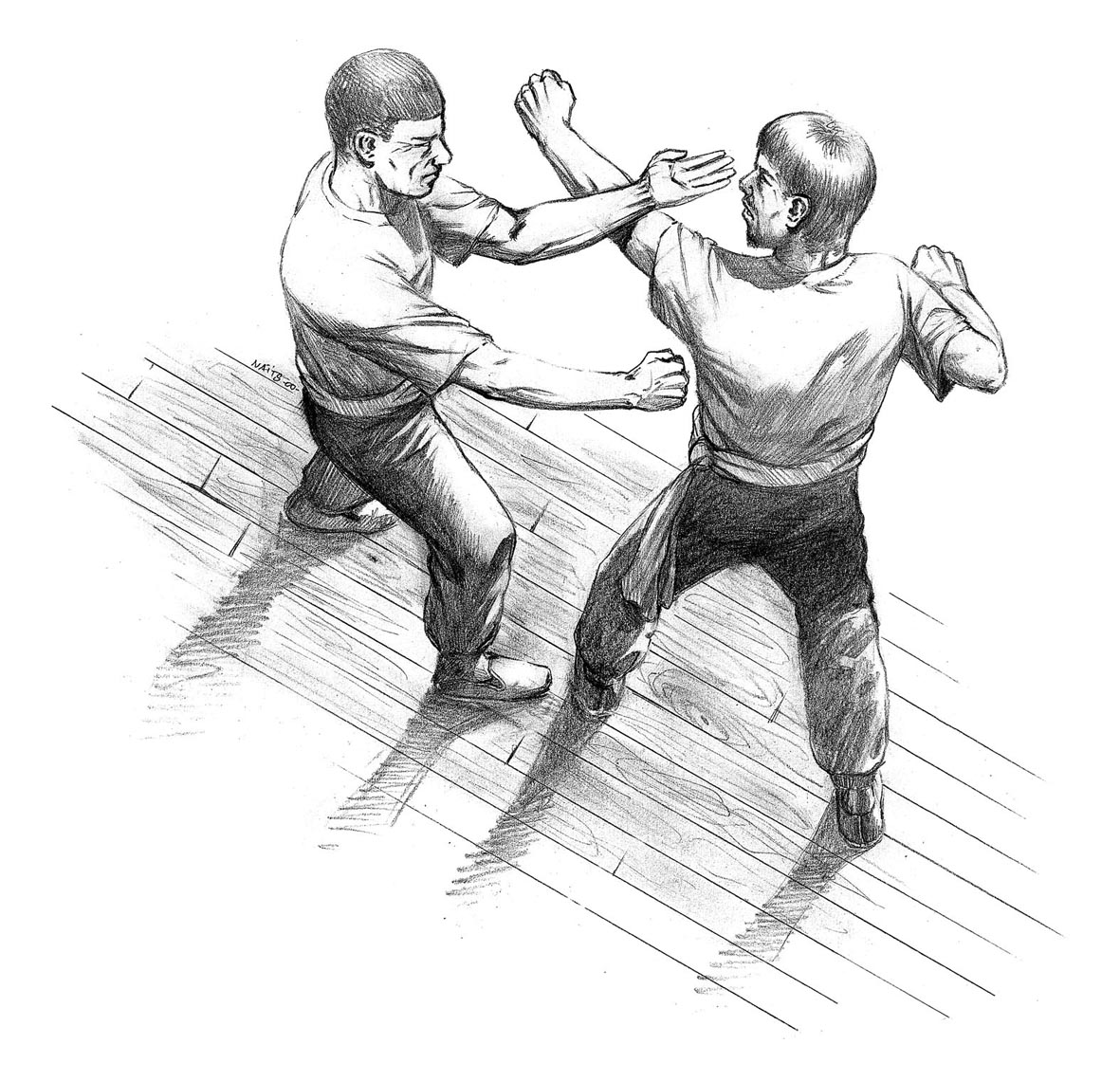

In his early twenties Dobrin was still looking for that elusive combat form to satisfy his innate aggression when, by one of those 'lucky accidents' which can shape a person's fate, Jay was driving around the streets of Hackney one evening when he noticed a large group of people entering a community hall.Intrigued, he parked up, entered the hall and was greeted with the sight of Brian Jones and Bill Newman drilling their students in the then-little known Chinese martial art of Wing Chun Kung Fu. Jay instinctively knew that this was that 'certain something' he'd been searching for; a martial art suited to his small stature, which encouraged forward aggressive momentum against bigger, stronger opponents at close range; utilising speed and deceptive hand movements.

Dobrin remembers: "I'd tried karate but the instructors used to bully people to get respect. Either that or we'd do kata after kata, with no explanation about the moves. If they'd broken it down and shown you what the individual movements were for and how they applied to combat I might've stayed but they didn't. They just showed you a kata" – [a series of rehearsed movements in a carefully ordered sequence] – "and then marched you up-and-down the hall for the rest of the night.

Then, when I saw Brian Jones training, it looked 'real'. Everything he and Bill Newman did was broken down and explained and you could see how the techniques could be applied to the street. I liked how Brian approached training; plus he had a very good army background and so he was a guy who'd 'been there and done it'. You respected him.

Bill was a very good fighter as well. There was nothing fancy or 'showy' with what they did. Brian had trained in Wado-ryu Karate, Judo and Tai Chi, as well as Wing Chun Kung Fu and so he used to mix it up. At the same time that Bruce Lee was creating Jeet Kune Do and telling people to train in different systems and 'take what you want' from each style – Brian Jones was doing it over here."

However, Jay's aggression nearly curtailed his training on the very first night. Frustrated by his lack of success when sparring with Bill Newman, Jay lost his temper and charged at Newman, head down and fists flailing. Newman simply sidestepped; grabbed Jay by the hair and then drove his knee sharply into Dobrin's jaw, knocking him unconscious.

However, Jay's aggression nearly curtailed his training on the very first night. Frustrated by his lack of success when sparring with Bill Newman, Jay lost his temper and charged at Newman, head down and fists flailing. Newman simply sidestepped; grabbed Jay by the hair and then drove his knee sharply into Dobrin's jaw, knocking him unconscious.Jones and Newman carried Jay into the dressing-room; 'revived' him and then promptly announced that he was 'barred' from the dojo because of his angry demeanour. Undeterred, a chastened Dobrin returned every night for three months and each time he was refused entry by Jones and Newman until finally Brian relented and – with a final warning as to the consequences of again losing his temper – allowed Jay to commence his Wing Chun training.

Initially, Jay trained three times a week but, as the atmosphere of friendliness combined with discipline and martial skill began to seep inexorably into his blood, Dobrin increased his training until he was working out five nights a week at the club and then training privately with Jones and Newman at weekends.

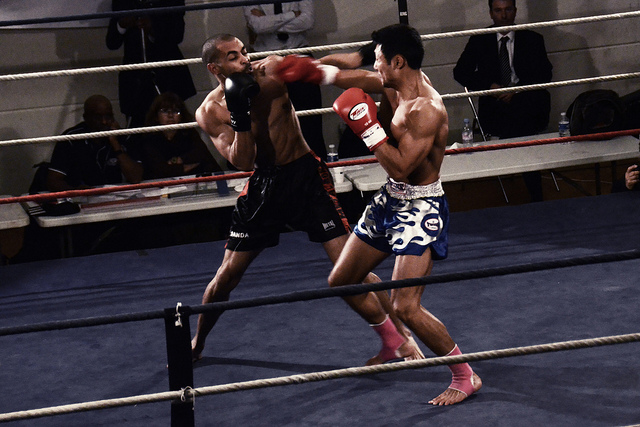

In the 1990's Geoff Thompson shocked the martial arts community when his club's 'Animal Day' training sessions became public. Thompson's belief was that martial art techniques needed to be pressure-tested in order for the student to have complete faith in their working in a street-fight situation. The obvious way to do this was to fight and see what techniques worked and which didn't under pressure. These gym wars could only be stopped by knockout, choke or submission; there was no time limit.

Initially, traditional martial artists were appalled at this seeming savagery but, as more and more clubs began to adopt similar strategy and 'no-holds-barred' fighting tournaments exploded into popularity around the world, it became obvious that serious martial students wanted to test themselves in a way that accurately represented actual combat. And yet, students from Brian Jones's club had been doing this since the early 1970's.

Initially, traditional martial artists were appalled at this seeming savagery but, as more and more clubs began to adopt similar strategy and 'no-holds-barred' fighting tournaments exploded into popularity around the world, it became obvious that serious martial students wanted to test themselves in a way that accurately represented actual combat. And yet, students from Brian Jones's club had been doing this since the early 1970's.II. 'Welcome to Fight Club'.

Once a student of Jones and Newman had reached a certain level of proficiency he was invited to attend the Sunday afternoon 'Behind Closed Doors' sessions. Fighters from other styles and systems were invited to come and test their skills against like-minded individuals. Upon entering the Barn attached to a pub in Hackney, everyone stripped to their waist and gathered in a circle. None of Jones's students displayed their coloured belts. A fighter would be judged purely on his level of skill in combat and not by the colour of his belt. It was merely two men battling each other until knockout or submission decided their fate.

States Dobrin: "The hardest guy to fight is a boxer. They train their hands constantly and they're used to taking punishment. They get punched in the face all the time and they'll accept those punches in order to get up close and land their own. Most martial artists aren't used to getting hurt. That's why so many people are now training in Mixed Martial Arts. In MMA you have to take punches; you have to take kicks and you get thrown to the floor. It's very physical and most martial artists today don't want that kind of pain. They want to train techniques and then go home – they don't want to spar or fight – and that's why they'll never truly know whether their techniques will actually work in 'real life' or not.

Most people discover that they're not anywhere near as good as they thought they were, because they can't handle the fear – the adrenalin rush. But that's a good thing to discover. Better you find that out in the gym than on the street.

There's always someone quicker, bigger and stronger than you. There's no guarantee that you'll stop that punch they throw at you. There's no guarantee that your knife defence technique will actually work under pressure. If someone knows what they're doing with a knife you'll never get it off them. You'll just get badly hurt trying.

With some street-fighters, they only know three or four techniques but they've honed them to perfection and those three or four techniques will be enough to beat you – even though you've learnt sixty-four different techniques in your training. You haven't got their mental attitude.

Once you're frightened, 80% of your techniques won't work. That's why it's so important to learn how to fight under pressure. If you don't know what real fear feels like then how can you hope to make your techniques work?

In a controlled environment your partner can knock you to the floor and show you what they'd do to you whilst you're hurt. But, they're not actually going to do it. At least you'll get that fear though, of being hit and hurt and know how you'd feel.

A lot of these guys who are kickers don't realise that when they're really nervous and their legs are shaking, they'll be lucky to make their feet move at all, let alone perform a head kick. There's nothing wrong with knowing your limitations. I've known some guys who were really good fighters in the gym but they couldn't do it on the street. If you know your capabilities you can act accordingly. With many people who want to learn how to fight, you'd be just as well telling them to hang a heavy punch-bag in their garden and keep punching it for as long and as hard as they can, day-in and day-out. At least if they can punch hard they've got a chance.

You can teach people about pressure and give them some basic techniques but, if someone hasn't got the mental strength, then all of the techniques in the world won't help him; he'll never be able to make them work under pressure. If someone puts their hands on me I'm gonna hurt them, but you can't teach everyone to react like that and it's not always appropriate."

You can teach people about pressure and give them some basic techniques but, if someone hasn't got the mental strength, then all of the techniques in the world won't help him; he'll never be able to make them work under pressure. If someone puts their hands on me I'm gonna hurt them, but you can't teach everyone to react like that and it's not always appropriate."Over the subsequent years Brian Jones 'polished' his evolving personalised martial art system; using what he'd seen work in real combat and adding karate kicks and judo throws to his students' Wing Chun base; plus elements of Kun Tao Tai Qi – [ the Malay style of Tai Chi he'd learned back in the 1950's, during his army service in the Far East] – until, after a period of time, Jones's Wing Chun club became the renamed 'Chinese Boxing' club, which revolved around a hard-core of students, such as Jay Dobrin, who had helped him develop his bespoke style of martial art.

Due to his constant commitment to training and his aptitude to learning, Jay achieved not only black belt status; he became a fully-fledged fellow instructor to Jones and Newman; running the Friday evening sessions alone, just as they moved the club's headquarters to Stoke Newington.

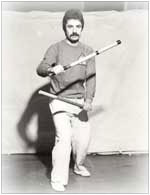

However, this tight-knit group of Chinese Boxers were about to undergo a seismic change of direction for, one night in 1975, a young man entered the training hall and changed their perception of 'what worked' in combat. The man's name was Rene Latosa and Britain was about to be introduced to the devastating Filipino martial art of Escrima.

III. Just when you thought you'd seen everything...

Rene Latosa began training in the Filipino martial arts in 1968, in the hotbed of American escrima; Stockton, California. For five years the young man trained with the legendary escrimadors Angel Cabales, Dentoy Revilar, Leo Giron and Maximo Sarmiento, learning the various ranges of combat and their personalised ways of using stick, knife and empty hand in battle. Ironically though, Latosa's escrima really blossomed only when he began training under the tutelage of his own father Juan, who'd been a dangerous no-holds-barred fighter back in the Philippines before moving to the United States.

Rene joined the US Air Force in 1973 and began teaching escrima to local police and SWAT teams, developing his own style of fighting and instructing along the way. In 1975, aged twenty-two, Latosa was stationed in England and it was at this point that he really began to advance his fledgling system; eager to start teaching it to a wider audience than previously.

Latosa approached several British martial arts publications and gave interviews on the unheralded Filipino fighting arts. However, weapons-based arts were secondary at the time to the 'kung fu boom' – inspired by the legendary Bruce Lee - and Latosa struggled to gain the widespread publicity he'd hoped for. Instead, he began touring martial arts clubs, offering to show his expertise to anyone interested in this 'exotic' art. One observer who was impressed with his skills was Bill Newman, who invited Latosa to teach his art at Brian Jones's Wing Chun / Chinese Boxing club.

Jones, Newman and Jay Dobrin were immediately captivated by Latosa's effortless use of weaponry – whether stick, knife, machete or, indeed, anything close to hand - and the three men trained regularly thereafter, with Rene; absorbing this strange but addictive 'new' art. [Sometimes Latosa would stay at Dobrin's home for the weekend and the two men would train constantly throughout.]

Dobrin recalls his first meeting with the physically imposing Latosa: "Brian and Bill were – as I say – good fighters, but none of us had ever seen anything like this. He said to us; 'Try and hit me with this stick'. You think to yourself, 'Okay' but you don't try to hit him too hard because you don't even really know him. He said; 'You're just wasting my time – you're not even trying to hit me' and so, after a while, we were really trying to hit him – smashing our sticks down hard but he was blocking everything.Then he began to block and follow through – not actually hitting us but showing us the counter-strikes. Once we'd gained in confidence and trusted his control, he brought out the blades and told us to try and cut him with them. He assured us that he'd be fine and that he'd control his counters and we wouldn't be hurt, but it still didn't give you too much confidence, because you'd only known the bloke for a couple of hours and now he's got a big blade in his hand. But, he was as good as his word. He was really good at what he did but he was a little intimidating to train with. Left or right hand – stick or blade – he could use any weapon."

After this period of intensive training Latosa awarded Jones, Newman and Dobrin their full instructorships in Escrima; the first such qualifications given in Filipino martial arts in Great Britain. Firmly in the grip now of 'escrima fever' the three men – along with Rene – formed the Philippine Martial Arts Society (PMAS) in 1976, with the aim of propagating the art beyond the confines of London. However, Rene received an invitation at this time from Keith Kernspecht, in Germany, to demonstrate his art to his Wing Chun students and Latosa saw this as his opportunity to expose Europe to the Filipino martial arts.

After this period of intensive training Latosa awarded Jones, Newman and Dobrin their full instructorships in Escrima; the first such qualifications given in Filipino martial arts in Great Britain. Firmly in the grip now of 'escrima fever' the three men – along with Rene – formed the Philippine Martial Arts Society (PMAS) in 1976, with the aim of propagating the art beyond the confines of London. However, Rene received an invitation at this time from Keith Kernspecht, in Germany, to demonstrate his art to his Wing Chun students and Latosa saw this as his opportunity to expose Europe to the Filipino martial arts.So it was that Latosa and Bill Newman ventured into Europe together and their student base exploded as they toured the Continent giving seminars; the popularity of escrima skyrocketing as people were shown its devastating efficiency.

[Latosa eventually returned to the United States and worked upon refining his system. Originally simply referred to as 'escrima' it became officially titled Combat Escrima in 1982, in order to denote the fact that it was a powerful, aggressive system. However, the disadvantage of this tag was that sometimes brute force and all-out aggression detracted from the subtler aspects of the art and thus – to avoid this assumption that sheer power would always prevail - it became, initially, Latosa Escrima and then Latosa Concepts.]

IV. BIFF.

By the late 1970's Jay Dobrin had received his instructorships in both Brian Jones's Chinese Boxing system and Rene Latosa's Escrima; at which point Latosa advised Jay to travel to America and train with some of the same instructors who had helped shape Latosa's own fighting style and so Dobrin duly journeyed to the US and experienced first-hand the lightning weapons skills of the likes of Leo Giron and Dentoy Revilar. Upon returning to England Jay decided to 'strike out' on his own. Rene and Bill were exposing the little-known art of escrima to new European students; whilst Brian Jones was content to continue running his Chinese Boxing clubs in London.

Jay's idea was to start blending the Chinese Boxing and the Escrima together, so that they became virtually one art. In this way – although they could still be taught as separate systems; particularly for those who didn't wish to engage in a weapons-based art – the practitioner could merge seamlessly from one art to another; picking up or discarding a weapon. The basic concepts from each system thus became a single concept, based around 'flow' and understanding fundamental body mechanics.

Initially under the banner 'Inner London Martial Arts Society', this quickly became redundant as Jay's reputation as a top-class martial artist spread and he was asked to start giving demos and seminars both nationally and abroad. Soon, Dobrin was spending lengthy spells in Europe, teaching armed forces personnel and civilians and this relentless travelling led to him renaming his clubs the British and International Fighter's Federation, [BIFF]; an acronym which immediately caught the eye.

By the mid 1980's Jay and his senior student / instructor in both systems Phil Chenery were amongst the hardest-working martial artists in Britain; constantly journeying to Europe; teaching the Finnish Army knife and other bladed weapons strategies and establishing BIFF clubs, run by European representatives of Dobrin's system, in Finland, Belgium and Germany. Also, established and highly-graded martial artists were calling upon Dobrin and Chenery to teach their students Escrima, as a complement to their karate or jiu jitsu training and it was during the 1980's and early '90's that Dobrin and Chenery established their awesome reputation for live seminars.

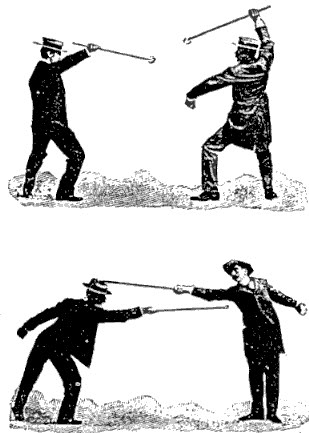

Very few people were using 'live' - [real] - blades in those days and the sight of Jay swinging a razor-sharp machete at Phil's head and then deftly parrying a balisong knife strike brought audible gasps from the spectators and their use of sticks and empty-hand sparring at full pace and heavy contact was a breath-taking spectacle. [Indeed, after one carefully rehearsed demo, in which Jay had 'battered' the willing Chenery for several hours, for the spectators delight, a barmaid who had watched the demo refused to serve Dobrin in the bar afterwards; claiming that he was 'horrible for what he'd done to that poor man.']

Dobrin has very definite ideas around why people should train with real blades: "We can't even get into a Sports Centre in England now. They won't allow us to use 'live' blades. We're limited as to where we can train. A couple of times recently we've done demos and as soon as we've pulled the live blades from our bags, they've gone; 'Oh, you can't use those here.' So we've replied; 'Well, we can't do the demo then.' There's nothing that makes us any different from any other Escrima system, once you take the live blades away from us. Our pedigree is that we're known for using 'live' weapons. That's what makes us different.

Most people think of escrima now as 'stick-fighting', because that's all they really see. But it's so much more than that. The only knife-work they see is with rubber knives and that's not 'real' Escrima.

Most people think of escrima now as 'stick-fighting', because that's all they really see. But it's so much more than that. The only knife-work they see is with rubber knives and that's not 'real' Escrima.The difference with a live blade is not only that you worry about being cut but you worry about accidentally cutting your partner. Whereas, with a rubber blade, you don't worry about who you're partnered with. With a live blade, that middle-aged lady suddenly becomes dangerous. Give her a rubber blade and everyone would partner her.

These people who train with rubber knives don't do anyone any favours. I've done courses where I've stood in the middle of the room, with a rubber blade and invited anyone to come out and fight me. They all come out and start throwing kicks and punches at you and then you stop and say; 'Hang on a minute'. I then go over to my bag, drop the rubber blade and pick up a real blade. Then I walk back over to them and snarl; 'Come on then' and they don't move. Walk towards them and they run away. They daren't throw a punch or a kick because they know I'll cut or stab their arm or leg. They completely change their attitude.

The great thing about live blades is, they're an 'equaliser'. Whether you're six foot four or four foot four, you're dangerous with a live blade. Everyone is equal.

On the street, that skinny thirteen year-old knows that he can get whatever 'respect' he wants from you, with a knife in his hand. With a blade against your throat you'll give him whatever he wants. A knife makes anyone dangerous. That's why I think you should train with live blades; so that you get that fear and you know what to expect if someone pulls a knife on you. Obviously, you need certain rules in a training environment; otherwise one of you could just pick up a knife and throw it at the other person. As long as you understand that on the street, there are no rules.

Some people get really good with the sticks but you're less likely to be attacked with a stick and less likely to be carrying a big stick around with you. It's great if you're good with a stick but will it really help you as much – in real life – as training with a knife? I remember years ago, I was training some Army guys, along with this very good 4th Dan Black Belt unarmed fighter. One of the soldiers asked him; 'What would you do if someone broke into your house at night?' He replied; 'Well, I keep a stick beside my bed, so I'd use it if I had to'. The Army guy was shocked. He said; 'What do you need to use a stick for? You're a really good fighter', but what he didn't understand was that it's an instinct to pick up a weapon. It doesn't matter how many years you train, in a situation like that you'd revert to what 'feels right'. Pick a stick - or other weapon up – because how do you know how many people there are downstairs, or if they're armed?

Ultimately, you should do whatever makes you happy. If all you want from your training is to have a bit of a workout and then enjoy a beer with the guys afterwards, then fine. But if you really want to be a fighter and know how to defend yourself on the street, then you need to face realistic situations in your training."

Training with Dobrin and Chenery was not for the faint-hearted. Once shown a block; if a stick was aimed at you, you were expected to block it. It was the 'traditional' Filipino way of teaching the art; whereby a rap across the knuckles with a hard stick was the fastest way to cure a defensive error.

Likewise, 'live' blades began with slow, sweeping movements and then gradually picked up velocity, as the student understood the flow of the drills. Nevertheless, it was usually the adrenalin coursing through their veins which enabled them to 'pass' and parry the 'live hand'; for one small mistake in timing could be very painful. In truth, training injuries were minimal, due to the high standards of instruction from Jay and Phil; although 'accidents' did happen.

Recalls Dobrin: "I've been cut and stabbed but nothing serious. This was in demos, mainly. I've also broken a few bones – toes, ribs, my nose a few times – doing the Chinese Boxing." [Laughs.] "We were told we could 'never teach again' in Sweden. I dragged a blade across Phil's throat, in a demo. I wanted it to look realistic but I pressed too hard and you could see beads of blood across his throat. When we finished the demo they told us that we were banned from doing any further demos in the country."

As the years passed Dobrin continued to refine his systems. Still referring to the unarmed side as Chinese Boxing, Jay had mixed Wing Chun trapping and sensitivity drills with Cadena De Mano – the unarmed side of Escrima – along with karate and Wing Chun kicks and strikes. This close-range system, he believed, could thus be used and adapted by any body-type; regardless of height or weight. Likewise, Jay took the essence of Latosa Escrima and adapted it so that it flowed and intersected with his Chinese Boxing; making them inter-changeable.

Today, the sixty-two year old Dobrin is still very fit and active and recently received his Master's grade from his old mentor Brian Jones but is cynical about grades and titles in martial arts. Dobrin reflects: "It's embarrassing for me. To be a 'Master' of something means what? You've 'mastered' life? You've achieved ultimate wisdom? You've mastered Martial Arts? To this day, although I still enjoy my training - and I know I'm good at what I do – I still don't think I'm good enough. I could be better...I want to keep training; keep learning new things. I can see how being a master blacksmith or a master glass-blower can be a substantial thing; they can prove their mastery of these crafts. But how can someone prove they're a master at fighting? I don't feel any different now to how I've always felt. Getting a Master's grade didn't make me a different person.

Today, the sixty-two year old Dobrin is still very fit and active and recently received his Master's grade from his old mentor Brian Jones but is cynical about grades and titles in martial arts. Dobrin reflects: "It's embarrassing for me. To be a 'Master' of something means what? You've 'mastered' life? You've achieved ultimate wisdom? You've mastered Martial Arts? To this day, although I still enjoy my training - and I know I'm good at what I do – I still don't think I'm good enough. I could be better...I want to keep training; keep learning new things. I can see how being a master blacksmith or a master glass-blower can be a substantial thing; they can prove their mastery of these crafts. But how can someone prove they're a master at fighting? I don't feel any different now to how I've always felt. Getting a Master's grade didn't make me a different person.I got my 8th Dan Black Belt from the Amateur Martial Association, simply because there are other people, less experienced than me, but with a higher grading and so the AMA didn't think this was fair." [Laughs.] "There aren't eight Dan grades in Escrima or Chinese Boxing, so I don't even know what I'm supposed to be an 8th Dan in. When I was younger I'd enjoyed being a brown belt, striving to attain black. Getting all of the Dan levels didn't mean anywhere near as much to me as getting to black belt. That's when I stopped worrying about grades. Personally, I'd rather people didn't grade and they just trained for the enjoyment of it. Over the years you know whether someone's any good or not but...people want to take grades; they want to see their progress. I've never worn my black belt. I've always said to my guys; 'If you don't wear a belt, people can't judge you, when they walk in'. People should be judged purely on their ability to fight."

[Anyone wishing to contact Jay Dobrin, for demos or private training, can do so via www.biffuk.com

David Weeks is a friend and former student of Jay Dobrin and is the author of 'ESSENCE OF A MAN: a Study in Male Violence and the Use of Weapons'. Available via Amazon.com or Kindle. ISBN 9781468072815 ]