On June 15, 1963 , US Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Ambassador Averill Harriman and British Foreign Minister Douglas Home flew to the Soviet Union to meet with Chairman Nikita Khrushchev and Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko in order to finalize a treaty ending atmospheric, underwater and outer-space tests of nuclear weapons. The Limited Test Ban Treaty [LTBT] was the first major multilateral arms control agreement of the Cold War, a goal that had eluded them for over five years. Back in Washington, Dean Rusk said they may not have achieved real detente, but "at least they had a hunting license for it."

Khrushchev had not only agreed to a very few on-site inspections, he had relaxed his longstanding demands for a new German 'peace treaty. In March 1958, the Soviet Union proposed talks for a treaty to limit nuclear testing. The invitation was accepted by the United States and Britain, but talks soon stalemated on verification problems. In November 1958, Khrushchev issued an ultimatum that the Western allies leave Berlin and East Germany [GDR] control all access to Berlin, which would become a 'free city.' The carrot he offered was progress on nuclear arms-control. A test-ban would be a starting point, especially in the face of growing public concern after intensive high yield hydrogen bomb tests.

All the nuclear powers [US, UK, and USSR] had an interest in curbing the expensive and dangerous escalation of nuclear weapons development. Public alarm, especially in Britain, increased pressure for a test ban. The United States and Britain had to take the lead in Berlin and test ban diplomacy. President Dwight Eisenhower acknowledged that Berlin might be "the catalyst" for a test-ban in 1959 meetings with Khrushchev that led to an attempted 1960 East-West summit in Paris. Despite Soviet stubbornness on inspection, Eisenhower intended an end run around the Berlin issue to get a test ban, but the U2 incident derailed the unpromising summit. Khrushchev had higher hopes for his June 1961 Vienna meeting with President John Kennedy, but could not resist bullying the novice President over Berlin, trampling hopes for test ban progress.

Vienna led to Kennedy announcing major US arms buildups in July and Khrushchev approving construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961. Military contingency plans on both sides spelled out nuclear options more precisely than at any point yet in the Cold War, making deadly clear the quick and probable escalation from battlefield nuclear use to general nuclear war. Despite emerging realization of how futile nuclear deterrence might prove, strategic doctrines did not change and escalation continued. Test-ban prospects in latter 1961 were sidelined towards the cumbersome auspices of the United Nations.

Vienna led to Kennedy announcing major US arms buildups in July and Khrushchev approving construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961. Military contingency plans on both sides spelled out nuclear options more precisely than at any point yet in the Cold War, making deadly clear the quick and probable escalation from battlefield nuclear use to general nuclear war. Despite emerging realization of how futile nuclear deterrence might prove, strategic doctrines did not change and escalation continued. Test-ban prospects in latter 1961 were sidelined towards the cumbersome auspices of the United Nations. The Wall stabilized the refugee crisis and met no resistance from the West. Emboldened by listless Western response and hoping to quiet Chinese taunts, Khrushchev authorized new Soviet H-bomb tests two weeks later. These high-yield tests included the infamous 40 megaton Soviet device, 'Tsar Bomba', Earth's most powerful nuclear detonation yet. The US resumed testing in early 1962, with robust devices over 20 megatons. These explosions were not only much more dangerous in destructive potential but exponentially more toxic. Khrushchev and Kennedy's private 'Pen Pal' correspondence reflects their very real desire for a way out, with a Berlin solution as the key.

But the US Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Llewellyn Thompson, perhaps the most trusted US envoy next to Harriman, was unable to break new ground that Rusk could explore with Gromyko at UN-sponsored arms-control sessions in Geneva in March 1962. Although inspection issues froze the public ENDC discussions, in private, Gromyko made it clear Berlin was still the big hurdle to a test ban. Talks with new Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin and Rusk in Washington and new US Ambassador Foy Kohler in Moscow were equally frustrating. The Soviets now wanted Berlin negotiation mainly to cover Khrushchev's next adventure, the emplacement of ballistic nuclear missiles in Cuba. Khrushchev may have realized that the West would offer no more concessions. He decided that if the US faced the same danger the Soviets felt from West German missiles, they would change their mind on Berlin and arms-control.

After the effective end of negotiations by August 1962, came another wave of Berlin harassments and then the Cuban missile crisis. Khrushchev was forced to withdraw his missiles, though he salvaged an unnecessary US concession to remove its own missiles from Turkey. Prestige shattered, Khrushchev was never again able to regain momentum on his Berlin campaign. He had other problems. Agricultural failures, military escalation, and shortfalls in consumer goods production stirred domestic discontent. Schisms in the Communist bloc abroad encouraged hard-line rivals, including his protégé Leonid Brezhnev.

Khrushchev asked the advice of former American Ambassador, Averill Harriman, visiting Moscow in April 1963. Khrushchev downplayed the importance of a new German peace treaty. All the Soviets wanted was the "normalization" of Berlin. Harriman told the Chairman he should leave Berlin alone and "come to an agreement on a test ban." He told Harriman they could work out a treaty, contingent on a Berlin agreement. Harriman said he "would not buy a pig in a poke." The two issues had to be discussed separately. Khrushchev joked that Harriman was "an old diplomat who knew how to talk without saying anything."

Kennedy issued a public call for better relations with the Russians, including nuclear arms control, in a June 9 speech. Khrushchev appreciated Kennedy's remarks and, on June 20, approved a 'hot line' direct telephone/teletype link with the United States for better crisis communications. He was less enthusiastic about Kennedy's remarks a week later in Berlin. Kennedy enjoyed a thunderous reception and stopped briefly at Friedrichstrasse Crossing, site of General Lucius Clay's November 1961 tank standoff, but did not tour the Wall. His famous "Ich bin ein Berliner" speech was rapturously received, but the Wall would stay.

The groundwork for serious test-ban negotiations had been established with US Arms Control and Disarmament Agency head Glenn Seaborg's visits to Moscow in the spring. Harriman was chosen as the US representative, with Undersecretary Carl Kaysen providing assistance. The UK's Lord Home would also participate in the talks. Harriman was uneasy that test-ban talks would start on July 15, with Khrushchev's discussions with the Chinese set for several days later. Khrushchev complained to Macmillan about Kennedy's tough talk in Berlin and suggested a test-ban be contingent on a non-aggression pact (NAP) for Central Europe.

The July 16 meeting in Moscow was relaxed and friendly, but Khrushchev did bring up his German issues and the NAP. He said a new arrangement would benefit East and West, while deflecting future German conflicts with the United States. Khrushchev intimated that there were several areas, "corns," that could be stepped on, where the Soviets could apply pressure on the West to encourage a peace treaty. Harriman replied that "as long as Khrushchev said it with a smile, he was not taking it seriously."

Lord Home and Rusk met again with Gromyko in Moscow on August 6. Gromyko wanted to discuss Germany and West Berlin. He said the West's proposals "reeked of mothballs ... this could go on for 10-25 or even 100 years." Alluding to the improved seismic monitoring which had convinced the West to lower their demands for in-country inspections, he added, "there was no known instrument that could detect progress in these [Berlin} discussions." But as much the East German and Soviet leadership resented West Berlin's survival as an island in a Communist sea, the US and Britain could not walk away from Berlin without suffering massive loss of confidence. Rusk said the West Berlin garrisons were necessary to ensure access and posed no threat to the "several Soviet divisions in East Germany... [it was] almost a waste of time to go on if this were not accepted."

Lord Home and Rusk met again with Gromyko in Moscow on August 6. Gromyko wanted to discuss Germany and West Berlin. He said the West's proposals "reeked of mothballs ... this could go on for 10-25 or even 100 years." Alluding to the improved seismic monitoring which had convinced the West to lower their demands for in-country inspections, he added, "there was no known instrument that could detect progress in these [Berlin} discussions." But as much the East German and Soviet leadership resented West Berlin's survival as an island in a Communist sea, the US and Britain could not walk away from Berlin without suffering massive loss of confidence. Rusk said the West Berlin garrisons were necessary to ensure access and posed no threat to the "several Soviet divisions in East Germany... [it was] almost a waste of time to go on if this were not accepted." When Khrushchev met the foreign ministers at his dacha in Pitsunda on August 9, he said they must now turn to the German problem which could be fixed with his peace treaty. Rusk replied that it was not up to the Soviet Union or Western allies whether the Germans should accept political division. Neither the US or USSR really wanted a unified Germany, nuclear or not. Vladimir Zubok, who has explored Soviet archives perhaps more than any other scholar, says Kennedy had Harriman ask Khrushchev about possible preemptive strikes on Chinese nuclear weapon facilities, but this approach was rebuffed. Khrushchev was unwilling to make such a break with his Chinese rivals.

On August 15th, Nikita Khrushchev signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty with Rusk and Home in Moscow, simultaneously with Kennedy and Dobrynin in Washington and Macmillan in London. Other nations followed suit when the treaty was introduced at United Nations General Assembly sessions in September 1963. Unfortunately, the nations most likely to develop nuclear weapons such as France, India, Pakistan and China, refused to sign the treaty. France was tied to the US and Britain in Berlin but had stymied test-ban negotiations throughout the crisis.

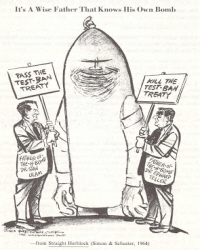

The draft Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) fell short of the comprehensive ban initially sought. The LTBT produced intense political criticism in the United Sates and faced tough Congressional review. The test-ban agreement forbade nuclear tests in the atmosphere, underwater and outer space, but not underground. The signatories also agreed not to assist or participate in tests by other nations. A final sticking issue was US insistence on a withdrawal option, tied specifically to perceived breaches in treaty observance.

Sergei Khrushchev says his father was very pleased with the Treaty, saying the USSR would retain an ample nuclear deterrent. President Kennedy enjoyed considerable prestige from the treaty but also incurred fierce anti-Soviet backlash. They never met again after Vienna. Perhaps if they had met for the signing of the Limited Test Ban Treaty, they might have sustained momentum for detente. They might, however, have, devolved into another Vienna-style dogfight, again scuttling chances for a test-ban.

As it was Rusk, Gromyko, Harriman, and Khrushchev brought home a treaty, which, though far short of expectations, still remains in force fifty years later. Khrushchev never succeeded in his Berlin campaign, but he brought the superpowers into unprecedented diplomatic engagement. That experience proved invaluable to completion of the Test Ban Treaty.

©Words - Dr Richard Williamson

Sources:

Much of this material is adapted from my book, First Steps to Detente: American Diplomacy in the Berlin Crisis, 1958-1963, published in May 2012 by Lexington Books. My book argues the Berlin crisis was a transformative sequence, introducing diplomatic pursuit of arms control centered detente, but also catalyzing a shift from the old multilateral East-West diplomatic approach to bilateral superpower engagement. My research draws heavily on national security file and personal papers collections of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas, the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts and the Lyndon B. Johnson Library in Austin, Texas, as well as central decimal series [cable traffic] collections at the US National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland. The Foreign Relations of the United States series (1958-60; 1961-63) on the Soviet Union, Germany and Arms Control,are essential sources, readily available collections of relevant primary documents with useful guidance. In addition, I make extensive use of a number of excellent, post-Soviet-informed secondary sources. The following titles are recommended:

Beschloss, Michael. The Crisis Years: Kennedy and Khrushchev, 1960-1963. New York: Harper Collins, 1991.

Bischof, Günter ; Karner, Stefan; and Stelzl-Marx, Barbara, eds., The Vienna Summit of 1961 Lanham: Lexington Books, 2012 [forthcoming]. [includes my article on the failed 1960 Paris summit with particular attention to test-ban prospects and Berlin linkage.]

Freedman, Lawrence. The Evolution of Nuclear Strategy. London: Palgrave, 2003.

Fursenko, Aleksandr and Naftali, Timothy. Khrushchev’s Cold War: the Inside Story of an American Adversary. New York: W.W. Norton, 2006.

Khrushchev, Nikita S., ed. by Sergei Khrushchev. Memoirs, vol. 3, “Statesman”. Philadelphia: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007.

Khrushchev, Sergei. Nikita Khrushchev and the Creation of a Superpower. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007.

Seaborg, Glen. Kennedy, Khrushchev and the Test Ban. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983.

Tal, David. The American Nuclear Disarmament Dilemma, 1945-1963. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2008.

Taubman, William. Khrushchev, the Man and His Era. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2003

Vladislav Zubok. A Failed Empire Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007